In 1814 CE Britain had taken the Cape Colony from the Dutch.

Economic opportunities, especially the discovery of diamonds in the ground, prompted the British to expand their territory in south Africa.

Their growth brushed against the territory of the Boers and the Zulus.

Shaka had made the Zulu kingdom a military state several decades earlier.

In the late 19th century CE the kingdom was not so aggressive anymore, though king Cetshwayo, wary of his restless neighbors, sought to revive the military system of Shaka.

Despite a relative peace the British, Boers and Zulus kept on quarreling over their mutual borders.

The British south African colonial administration used these as a pretext for demanding, among others, that the Zulus disband their army.

This was of course out of the question and on new year's day 1879 CE war broke out.

The British, commanded by lord Chelmsford, moved first, invading Zululand with several columns over a wide front, to prevent the Zulus striking at their rear.

They wanted to score an early victory, so attacked in January, in the rainy season.

The bad weather slowed them down to a crawl, advancing 16 kilometers in 10 days.

The central columns, under Chelmsford's personal command, numbered over 4,000 men plus a number of civilians.

Almost all soldiers were armed with rifles.

A minority were hardened British regulars, the rest African auxiliaries who had received little training.

Most were infantry; the army also included some small irregular colonial cavalry units and a detachment of artillery with six field guns.

The Zulu impi numbered around 20,000, though only 10,000 - 15,000 took part in the battle.

They were armed with stone age weapons: spears and shields.

The Zulus had a small number of outdated rifles, yet these played no significant role.

The impi assembled at Ulundi, held a war council and then quickly marched south, covering 80 kilometers in 5 days.

Chelmsford reached Isandlwana hill and set up camp there, but did not fortify it because he was overconfident.

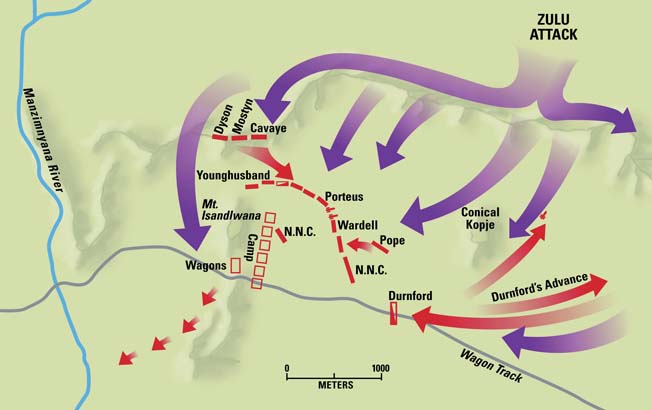

His scouts encountered the Zulus and he split his force in two, commanding the larger half to pursue them, while the smaller half stayed at the camp.

The Zulus retreated, luring him away, while their main force bypassed Chelmsford and advanced on Isandlwana.

They intended a surprise attack, however were discovered by British cavalry.

Immediately they switched from stealth to to attack, deploying in the traditional Zulu 'bull horn' formation, with outstretched wings.

The British formed a defensive line, keeping the attackers at bay with their firearms and artillery.

But they were being outflanked and forced to retreat into a tighter formation.

Some units ran out of ammunition, though most did not.

The Zulus advanced on all fronts and used their numbers to overwhelm the British.

They were briefly helped by a solar eclipse that darkened the battlefield for a short while.

Unable to shoot down all attackers, the British were forced into hand-to-hand combat where they had no advantage over the Zulus.

The last defenders had to fight back to back with their bayonets.

Some managed to break out in the south, as the horns had not entirely closed around the British.

Out of the 1,700 men strong camp garrison, 1,300 were killed.

Zulu casualties have been estimated at 1,000 - 2,000.

The Zulus probably deliberately drew away Chelmsford; it was his mistake to let that happen.

They used speed and surprise to overwhelm the British before the latter could set up a good defense.

Had the British constructed a laager of wagons, bristling with rifles, they might well have held out even while completely surrounded.

The victory at Isandlwana broke the British offensive.

However the Zulus did not exploit their success by cutting off the supply lines of the remaining columns.

They mounted an attack on a mission station at Rorke's Drift, but were repulsed.

The British retreated.

The government in London had not approved the first invasion, yet now felt compelled to launch a second.

The south African army was heavily reinforced and within a few months attacked again.

That time they won decisively, dismembered the Zulu nation and annexed their lands.

War Matrix - Battle of Isandlwana

Geopolitical Race 1830 CE - 1880 CE, Wars and campaigns